Kingdom of Warwick

Warwick is a recently formed kingdom which seceded from Alba in 2021, where it was a formerly a Duchy. The region, a large wedge-shaped tract of land encompassing the entire area between the northern border of Doomstadt and the true Goblin Wastes, has a long and tumultuous history, and only recently came under (or, in a sense, returned to) Alban authority by way of a mutual assistance treaty between His Royal Majesty King Michael Van Dance and the Northern Doomstadt loyalist faction under Her Majesty Queen Dolosus Mauvis in 2007.

The Kingdom is ruled by His Grace High King Sebastian “Jinx” Lledrithcath, also Baron of Tir Anwar, Wales, and his wife the Queen Olivia, from the capital city of Newcastle, in central Warwick. It is bordered on the south by Doomstadt, has its eastern extremity abutting the Dragonspine Mountains, and a rough northern border is determined by east-west tributary mountain ranges with innumerable names and descriptions according to disparate local traditions, which serve to divide Warwick from the utterly untamed, trackless, and magically twisted landscape of the Goblin Wastes beyond.

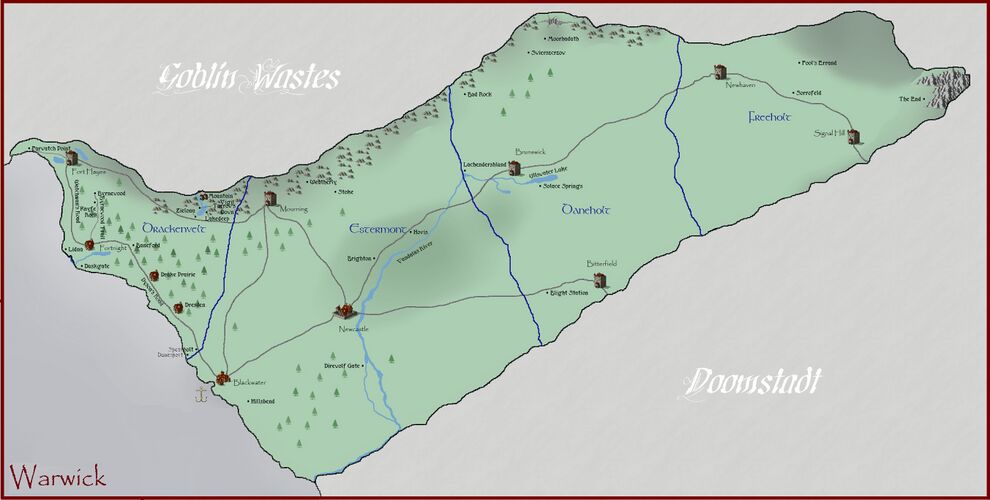

Warwick is itself divided into four Earldoms; Drakenvelt along the greater portion of the western coastline, Estermont for the southern extent of the coastline and eastward roughly a third of the Doomstadt border, Daneholt extending further into the east, and Freeholt anchoring the entire eastern end of the duchy. There are three large cities in the duchy, and numerous significant towns and fortifications.

Warwick is geographically and economically varied, with many areas being, perforce, entirely capable of self-sufficiency. Unlike Alba Proper, only a small portion of the vast amount of land in Warwick is formally incorporated into lesser lordships and settlements, leaving huge amounts of technically unclaimed real estate. This is not, however, to suggest that the real estate in question is uninhabited, and the flourishing populations of goblinoid races, barbarian tribes, wild creatures, and other dangers are a constant reminder as to why each lordship defines only that small area which it can reasonably defend.

The population is likewise varied, although there is a particularly strong representation of families who, in recent or distant generations, escaped bondage in Doomstadt and fled to the north in search of safety and independence. For this and other reasons there is a strongly independent frontier spirit about most populations of any significant duration within its borders. Though existence is brutal and fraught with dangers, the hard-won reward is freedom from oppression, a freedom not easily or willingly surrendered.

History

Prior to the arrival of the Thracian Empire, the lands adjacent to the Goblin Wastes deemed reasonably habitable by the indigenous cultures fluctuated in broad, sweeping trends. At the time of Thracia’s arrival and conquest, the habitable portion extended even further north than it does today as the Wastes were, at that point, in what might be termed a decline. Trends have since reverse, however, and the amount of land claimable by civilized nations fell back over the generations to well south of the mountains that define the present border. The current shape of the land defined as Warwick may be evidence that the Wastes are again temporarily receding, or may only bear witness to the dogged tenacity of those inhabitants willing to fight to lay claim to even barely-survivable wilderness.

The Kingdom of Imagicka, formed in 1177 and lasting until 2001, could be considered one of the most stable and profoundly durable influences in the known history of Pangea except for one persistent element of disharmony. The land encompassing what is now the nation of Doomstadt and the Duchy of Warwick periodically throughout Imagicka’s history seceded or fought free of the greater kingdom before inevitably being reabsorbed into the whole at a later time.

When contained within Imagicka, both lands were considered the Earldom of Warwick. When independent, the nation of Doomstadt, homeland of the Endrani people, occupied a variable amount of territory which variously included all or some of what is now the present day Duchy of Warwick. Consequently, the territory of what is now Warwick would go through constant changes of administration, first being a unified part of Imagicka, then all or partly under the control of Doomstadt with or without lingering Imagickan influence, then all or partly ignored by any and all form of government, then reabsorbed into Imagicka once again when matters in Doomstadt inevitably deteriorated, due to their fractious and divisive internal politics, to the point where Imagicka could reclaim the wayward state. The amount of land taken and how political chips fell any given turn of this cycle determined whether the resulting land was termed Doomstadt or Warwick.

Treated by Doomstadt and Imagicka alike as a kind of buffer between civilization and the true Wastes, the folk that survived in Warwick tended to be tough and resourceful, able to cope fluidly with the dramatic changes that were constantly afflicting them both environmentally and politically. While Doomstadt may have nominally extended a little further than its present borders in recent history, for a great deal of the time the Endrani houses did not have a significant presence in what is now Warwick, as it was just too contentious to hold. The houses there were either slowly subsumed by more southerly houses or were for whatever reason destroyed or broken.

The most recent withdrawal of Doomstadt from the Kingdom of Imagicka came in 1978, after a dramatic mass-assassination of many of the ruling nobility. After the dramatic overthrow of the upper classes termed “The Night of Long Knives,” the new leadership in Doomstadt systematically drove all traces of the Royal Imagickan Army northward out of the lands they wished to claim, driving them into the insecure reaches of extreme Northern Warwick where, cut off from all aid or reinforcement, entire regiments of the Imagickan army were left essentially to rot for months on end, defending what they could of Imagickan territory in Warwick, before meaningful relief could arrive.

Lacking any significant presence, let alone military strength, in Warwick, Doomstadt’s elected borders after this time closely resembled those of today, leaving the territory of Warwick nominally under Imagickan control. The Imagickan Nobility, however, were not content with this scenario. As most of significant landholders in Warwick had other estates of value in other parts of the Kingdom, being isolated on the far side of hostile Doomstadt in the unforgiving environs of Warwick did not sit well with the ruling class. Most began a gradual but systematic abandonment of their territories there. The army, whose strength was dramatically depleted in the initial confrontations and the ruinous withdrawal, likewise dwindled and basically disappeared from Warwick by 1982, leaving the lands entirely abandoned except by those fiercely determined to retain their homes and lives. As Imagickan influence departed, Doomstadt crept northward by degrees, laying claim to as much as 20 or 30% of Warwick. Lacking interest in administering or protecting the dangerous and disconsolate wilderness, however, Doomstadt simply looted the lands they claimed and then left them alone as a semi-pacified buffer for years, only venturing northward to draw from the local or goblinoid populations to supply the booming slave trade.

It was only after almost 30 years of non-governance that the whole territory of Warwick was parceled and awarded to Alba in a treaty with Doomstadt, who had become embroiled in a civil war between the Northern Houses, loyal to Queen Dolosus and her progressive governmental stance, and the wealthier Southern Houses aligned steadfastly against them in conservative determination to retain the old practices. In exchange for direct assistance in this conflict, Alba was awarded all of Warwick, right up to the old Imagickan northern border and south not only to the border Doomstadt had claimed but in fact past it so as to include all those lands not actually held or maintained, setting the borders where they are today.

The arrival of Alba met with deeply mixed sentiment among the local populations. In a very real sense, Alba was the spiritual successor to the Kingdom of Imagicka, which dissolved under its own weight after the war of succession in 2000/2001. The nobility returning to lay claims in Warwick was of the same cloth, if not in fact some of the same families, that had abandoned the land thirty years previously. On the other hand, Alba represented a newer, less fragmented nation. Both settlement and occupation by military forces provided booms to the population and economy, and represented a chance for a far improved state of civil security in the new Duchy. Best of all, Alba represented a foil against the depredations of Doomstadt, which had been rampant as the civil war in that country raged on.

Some long-standing leaders or lords in their own right were retained or elevated under the administration of the new Duke, while voids in leadership or places where the authorities were hopelessly corrupted were filled with substantial grants awarded to Alban peers. Rumors of wealth and lost wonders to be discovered as well as the promise of abundant land that could, in theory, be farmed once pacified brought in enormous waves of settlement and many of the population centers doubled or even trebled in size practically overnight. The land was divided into the four Baronies along rough historic boundaries, and the effort was undertaken to assuage the fears and soothe the recalcitrance of the local people to harmoniously integrate the enormous new territory into the rest of the Kingdom.

Geography

Waterways:

The Duchy of Warwick includes a vast amount of territory and a great many geographical idiosyncrasies. The coastline, ranging roughly northwest to southeast, has few truly useful ports or natural harbors and is plagued by occasionally whimsical ocean currents and erratic weather patterns because of its proximity to the Wastes. By far the most substantial harbor is occupied by the sprawling international port city of Blackwater, in Estermont. Other smaller harbors do exist, and are settled, but none offer anything approaching the same degree of security or relative protection.

The most prominent and significant waterway in Warwick is the River Vandalus Already a powerful river where it finds its way through the barrier mountains to the north, the Vandalus splits Warwick in two, forming a portion of the border between Estermont and Daneholt before picking up additional volume from vast artesian lakes near Brunswick and proceeding down through the breadbasket of Warwick, a lushly fertile and hotly-contested hill country occupying central Estermont all the way to Newcastle. From there, the Vandalus descends into a lowland marsh country, creating swampy conditions where it forms an inland delta and divides in to the Lesser and Greater Vandalus. Between the two channels lies the ill-omened Keening Morass, a substantial island made almost entirely of dark bogs and suspicious things that discourage visitors. Because of its origins in the deep Wastes, the Vandalus water is less than perfectly healthy, particularly north of Brunswick, and has been attributed as the cause for a great many curiosities about the landscape. It is frequently regarded as cursed, or at least containing dreadful contaminants or magical poisons, but nevertheless serves to irrigate tremendous areas of farmland which are not altogether warped as a result. Strange and unusual creatures inhabit most reaches of the river, and swimming is a generally discouraged practice in all adjacent communities.

Shortly after the Lesser and Greater Vandalus reunite, the now truly enormous river converges with the equally large River Istros out of Doomstadt at a low-lying but dramatic cataract. The waterfall, while impressive, is difficult to access or see from its position near the edge of a large swampland, and is known by a variety of unfriendly and unflattering names to various groups influenced by it, most commonly “Woebegone Cascade” or simply “The Cascade.” This remarkable feature completely prevents river trade from reaching inland Warwick. From the confluence to the sea, the River Istros forms a portion of the southern border between Warwick and Doomstadt.

In central Warwick, the city of Brunswick lies near several artesian lakes, the most vast of which is Ullswater. The source for these lakes is underground, and their water is without question the most pure and healthy in the entire duchy, making the moor country around Brunswick some of the least impacted by Waste-warped anomalies. Ullswater itself is used as a refuge for the citizens of Brunswick in times of extreme hazard, and the small rock promontories that pepper the lake surface feature moorings that transform the lake into a veritable city of barges when Brunswick’s citizenry retreat there.

Other, smaller lakes dot the nearby landscape, and the White River, named for its rocky chutes and cheerful rapids, bears their water down to join the Vandalus.

Much of the rest of the duchy is of drier clime, but Drakenvelt has several notable water features. Fort Hayes is bracketed by the Barrier Lake and Lake Ripple, both very large and unusual lakes. As close as they are to the Wastes, it is theorized they were either created or influenced dramatically by magical contamination, and frequently roll as violently as the sea without any visible cause. A great many legends are associated with both bodies of water.

Near the town of Fortnight lies the simply named Fortnight Lake, a small body fed by streams and runoff from the Drakenburg which drains into an ocean inlet at Duskgate. Though a reasonable distance inland, tides and rogue weather can drive sea creatures into Fortnight Lake, resulting in a fairly unstable ecosystem that is occasionally visited by strange, hungry, or unwelcome denizens. Under favorable conditions bass, perch, bluegill, and large frogs can be found in abundance.

In Eastern Drakenvelt, the Wastefed River originates with innumerable headwaters in the peaks around Mountain Vigil, and drains into the Wastefed Lake, which supports several communities. Despite the ominous name, both lake and river are well regarded by residents and used as primary means of transportation between those communities. One curiosity to the Wastefed Lake is that its outlet is deep underground, creating a certain peculiar current that draws in the deep waters. Things lost in the water are, typically, never found. Ever. Also associated with the Wastefed Lake are innumerable legends of haunting and strange creatures much as one might expect, including at least one lake monster, several prominent ghosts, a mythical ruin of a city or fort at the bottom, and that it occasionally glows under a new moon. The Wastefed Lake is an abundant fishery, particularly populated by carp and pike.

Mountains:

Much of the northern border of Warwick is defined by barrier mountain ranges which reach out to and join the Dragonspine beyond the habitable boundaries of the duchy. Beginning near Fort Hayes in northern Drakenvelt and stretching eastward is a moderate, if somewhat inconsistent, range of mountains and mountainous country termed “The Crags” by the Watch. Less than a true range, The Crags are rough peaks, narrow canyons, and generally difficult country that is nevertheless quite passable to anything determined enough to get through and home to innumerable goblinoid tribes.

As The Crags extend east they join up with a much larger and more powerful range. From central Drakenvelt eastward to beyond Mourning is a towering, difficult to traverse range frequently called The Nine Towers, Hightower Mountains, or something similar, by those it protects. As impassable a barrier to the horrors of the deep Wastes as it is to any weak-minded adventurer destined northward, it has only a handful of viable passes, the best of which is crowned by the ever watchful fortified town of Mountain Vigil.

In west central Drakenvelt, near the town of Fortnight, lies an isolated range jutting up from the hilly landscape. It, too, is the subject of a great many local monikers, but officially it is titled the Drakenburg, and is visible from as far away as Fort Hayes to the north and Dresden to the south without difficulty. The range is steep and inaccessible from the southern and western foothills, but can be accessed from the Northeast. Contained within the shadow of the peaks is a central high prairie that becomes wetland much of the year and is regarded as extremely dangerous and possibly poisonous. Much of the Drakenburg is honeycombed by caverns and curiosities, and a single mining community, Atherstone, is tucked away in its high reaches.

Extending across most of northern Estermont are a collection of small ranges offering moderate protection but which extend significantly north of the border into a more formidable range which is, unfortunately, well in the Wastes and populated by monsters. The various ridges and ranges of Northern Estermont each has its own name, often associated with townships or notable events, but may be known by several colloquial designations. These mountains descend abruptly to give way to the river valley of the River Vandalus, which charges out of the north defining the border between Estermont and Daneholt.

The mountains to the north of Daneholt are lower but much more dramatically formed, sometimes interrupted by tremendous breaks in the peaks, queer canyons, and twisted formations. Most notable amidst these badlands is an enormous chasm at the northernmost point land claimed by Warwick. This fissure, Dane’s End, is more than forty miles in length, east to west, and in places several miles across, riddled with lesser cracks and canyons. Its depths are impenetrably deep and unexplored, and the span is completely impassible. Legend holds that Dane’s End is the site of an ancient battle between two inconceivably powerful, wicked mage lords in the distant past. Their conflict was so abominable, and the casual way they spent the lives of their followers so repugnant, that the gods themselves became enraged and sent Avatars to tear very land asunder in an earth-shattering quake, leaving the armies of the two lords separated by the impossible chasm. The names of the lords were then struck from time, so that none could ever remember or honor them, and they were cast into the pit, where presumably they linger in some dark manifestation that causes plumes of poisonous smoke and even ash to drift upward from the breach during times of ill omen.

Forests, Plains, Deserts:

Most of Drakenvelt is deeply wooded, and as a general rule the farther north one progresses the more twisted or unusual the woodlands will become. Mapmakers term the vast forests of Drakenvelt, some of which spill into Estermont, “The Black Woods” but that is a name not acknowledged nor used locally, where any small section of forest may demonstrate so unique a property that it demands its own name, such as “Burning Pines,” “Misery Valley” or “Orcwood.” In point of fact, if compelled to assign any name to the general area, most residents would simply be confused and term it “The Woods.” As well ask them to describe what they typically call the sky in their area, as it is so ubiquitous a feature.

Near Fort Hayes and northward into the true wastes the woods decrease and eventually cease in flat steppe country transitioning into a truly wasted, almost desert country, heavily populated by goblinoids, which is in part responsible for the strategic positioning of the Fort.

North of the “Black Woods” lies a rough hilly country that eventually becomes the Crags and the Hightower Range. South of the woods lies a coastal plain, generally called “Drake Prairie” though that name truly belongs to the small grain-growing settlement situated in the center of it.

Estermont is bounded on the west by the edges of the Black Woods, which also extend along the northern border. The central corridor between Blackwater and Newcastle is among the best-traveled and well maintained land in the duchy, composed mostly of wild grasslands. South of that corridor lies lush, well managed woodlands, but those woods quickly descend into boggy marsh and dire swamp country, eventually sinking to the inland delta and the dark expanses of the keening morass.

Upstream of Newcastle lies the lush river country, low hills and lavish farmlands that extend most of the way to Brunswick, which lies in somewhat higher moorland, interrupted by low limestone massifs and dotted with lakes. The countryside becomes increasingly erratic and unpredictable in the extreme east of Warwick and into Freeholt, much as when extending north towards the wastes, but Freeholt is largely scrub country, sagebrush, scabland, and the occasional low creosote wood. The northern end of Freeholt is outright desert, blasted and blighted countryside of sand and salt flats that extend deep into the Wastes beyond.

The south of Freeholt, and even parts of Daneholt, fare little better. Once blanketed by the rich forests that in some ancient time covered most of Doomstadt, the country was stripped to its bones and now is dry grass and scrubland verging on true desert that presses deep into the northern expanses of Doomstadt itself. Old abandoned pit-mines create darkly contaminated lakes, and little thrives there but the vultures.

Map

Organization of the Land

The Kingdom of Warwick is divided into four expansive Earldoms, each containing a number of smaller incorporated lordships. Unlike the well-mapped and long-claimed territories of the other Alban duchies, however, Warwick’s incorporated spaces comprise only a small fraction of its total lands, the rest essentially trackless territory containing freeholders, isolated and solitary communities, indigenous peoples, wild and uninhabitable lands, brigands, and danger of every sort imaginable. Each barony has within it centers of population that are of note, whether as large centers of commerce or society, important fortifications, or simple exemplars of their regional landscape. For simplicity, the following are subdivided regionally.

Drackenvelt

The western-most Earldom of Warwick is Drakenvelt, ruled by the Earl Walther Hulse of Mourning. While by a fair margin the smallest of the four baronies, Drakenvelt is nevertheless a very active and hazardous locale, guarding the western-most flank of the northern mountain ranges, the northern coastline, and a significant span of deeply disturbed woodland. Both as a result of its geography and because of more occult idiosyncrasies, Drakenvelt is a territory fraught with dangerous convergences of circumstance.

Fortnight

The most notable community in Drakenvelt is the small but prosperous town of Fortnight. Historically, Fortnight was for many years a kind of aristocratic penal colony which housed troublemakers among the peerage, non-inheriting extra offspring that could prove difficult, and voices of political dissent. These inconvenient persons were sent to Fortnight rather than executed, avoiding some of the social problems that would have resulted otherwise. Fortnight was at that time well within the established and pacified borders of a calm Imagicka but far too remote to allow for any of these rebellious youths and so on to be of political influence.

A massive incursion from the Wastes was cause to evacuate the area in 1712. Because of the general devastation being caused throughout Imagickan lands by the resurgence of the NulMagicus plague, the Army was unable to maintain the remote border. The commander of the prison, Lord Henrick Deyson, chose to stay behind and defend the border rather than evacuate, offering the chance to fight to his detainees as well. Many agreed, and Deyson led a band of roughly 300 of these former ne’er-do-wells deep into the heart of the invading forces, whereupon they were able to slay the Ogre Magi orchestrating the entire affair and break it apart. Thereafter, these same men went on to be pardoned by Queen Anne, and became the first members of the Night’s Watch, renaming the place of their former imprisonment Fort Night.

The town of Fort Night did not stand the test of time, but the ruins of the old keep and foundations of the settlement remained. And when Alba reclaimed the lands of Warwick, upon those foundations was built the modern town of Fortnight. Fortnight as it is today was founded by an expeditionary force of adventurous souls migrating from the infamous town of Scarborough in Southern Wales. Because of this, its population is uncommonly diverse, and only becomes more so with time as more of the same ilk inexorably find their way to the ill-fated community. Fortnight stands at a crucial point along the trade road that follows Drakenvelt's coastline, and frequently finds itself in the way of grave incursions working their way south from the Wastes.

The economy of Fortnight is diverse, with many of the local tradesman predating its founding taking up with enthusiasm the sort of crafts and trades that support a resident population with a solid core of trained fighters, mages, even ritualists. Sheltering under the wing of their fearsome protectors, the locals and farm folk consciously make the choice to stay in the line of danger for the sake of their homes, their freedoms, and their pride.

The lordship of Fortnight includes lands for many miles in all directions from the town itself, and includes a pivotal crossroads to the north, marking the branching-off of lesser roads leading to the towns of Lidna and Byrnewood. Annual markets and fairs are conducted in the summer at these crossroads, sometimes drawing merchants and custom from as far away as Blackwater.

Fort Hayes

Perched strategically between two large lakes, at the very north end of Drakenvelt lies the Nights Watch stronghold of Fort Hayes. This much-abused fortress houses members of the watch including the commander of all smaller outposts in the region, currently Commander Bradley. There are training and research facilities, as well as barracks and various amenities, but the extreme dangers posed by guarding what amounts to a funnel for all hazards that might creep southward have long kept any sort of township from arising around its oft-battered walls. With so much work to be done, and the Watch eternally shorthanded, the fort itself is seldom well-staffed and occasionally subject to being entirely overrun.

The two lakes flanking Fort Hayes are subject to many local myths and legends, with origins that range from ancient to entirely supernatural. To the west, Lake Ripple stretches towards the coastline, forcing the battered trail of Last Run to follow its northern shore on the way to the remote lordship of Farwatch Point. To the east, Barrier Lake points its uncanny finger towards the edge of the Crags, serving as named to blockade those who would come south to some extent. Both lakes are renowned for their supernatural properties, including that they at all times shift and sigh like the sea, or as though there were some constant force of disturbance seeking to well up from their centers, and Barrier Lake is particularly known for queer lights and uncanny mirages that play across its surface in certain seasons.

Other Communities

The very northwest point of Drakenvelt is anchored by the coastal town of Farwatch Point, an utterly isolated lordship that has existed for generations unnumbered in spite of what politics may say of the region. Sharing with much of their population a Norsk heritage, the Habreadth clan has ruled Farwatch for as long as any can remember, and for a place constantly under siege by every manner of goblinoid and indigenous hazard, it remains stalwart and even at times prosperous. The area is known to possess some decent gem mines, and bountiful coastal fisheries, and its people are renowned for being tough, implacable folk who will not give trust easily.

Southeast of Fort Hayes, due north of Fortnight, is the remote town of Byrnewood, nestled along the Byrnewood Trail linking the Watchman’s Road to the North Road. With a reputation for being a bit addled by their isolation in the deep woods, those of Byrnewood nevertheless stay on the map as an excellent source for exotic furs and a distinct red dye that is in constant demand, the secret of which is jealously safeguarded.

South of Byrnewood, in between where the Trail and Watchman’s Road run parallel, lies the Goblin town of Knyfe Rock, tucked against a vast rogue boulder that closely resembles a cultural hero. A pseudo-civilized community populated entirely by the goblins known as Blackears’ Band who have become Alban citizens, this settlement is young and its future is uncertain.

The Byrnewood Trail and Watchman’s Road merge at the Crossroads within the lordship of Fortnight, joining Deyson’s Road south and the small dogleg leading to the coastal settlement of Lidna. Abutting Fortnight on one side, Lidna is known to trade in fine local silver and keep very much to itself, avoiding involvement in pretty much everything.

South along the coast, guarding the mouth of the ocean inlet leading to Fortnight, is the lordship of Duskgate, so named for the narrow mouth of its small, shallow bay which for most of the ear neatly frames the evening sun descending onto the western seas. A small community with a long and troubling history, Duskgate is presently under the management of a figure of local fame, once the free-roving “Lord of the Marches” responsible for many years for keeping much of Drakenvelt safe and relatively organized, now newly-minted vassal to the Alban Crown, Lord Ahren. Duskgate’s mill provides lumber for many of the nearby lordships, and its citizens are known for being rowdy and at times profiteering.

Farther down the coast in the very heart of Drakenvelt lies Drake Prairie, the largest single lordship in the barony and a breadbasket in and of itself. Sheltered by its strategic location and held as a treasure by all neighbors for its substantial fields and orchards, Drake Prairie easily suffers least from the ravages of the wild country. Its primary village is called Green's Hollow.

North of Drake Prairie, inland along Deyson’s Road, lies Baneford, so named for being situated on a notoriously unpleasant crossing in the seasonally tumultuous little river passing through. Baneford is known for its quarry and stoneworkers, and notable for the ancient watchtower crowning the village, home of the local Lady Berant and invaluable defensive resource.

Farther down Deyson’s Road still is the prosperous and large lordship of Dresden, comprising both the town of Dresden itself and the more remote village of Legnica. Brewers and Vintners make a sound living in Dresden, and its intoxicants are well regarded throughout Warwick.

South of Dresden along the coast is Gera’s Point, home of the notorious Lady Lizann Gera, a formidable Endrani ex-pat. Her closely managed estate is rich in rare earths and mineral resources, as well as pearls gathered by the gutsy divers in her employ. If Gera’s Point is known for anything, it is driving a hard bargain.

At the very south end of Drakenvelt, within a day’s travel of Blackwater, lie the twin settlements of Spearholt and Danesport, the former along Deyson’s Road and the latter against the coast. While Spearholt has a decent textile industry and is the only decent place to stop for the night on the way north from Blackwater, Danesport resides without complaint in total obscurity.

In the mountains of northeast Drakenvelt perches the fortified town of Mountain Vigil, on one of the few questionably survivable passes through the Hightowers. Overlooking much of the surrounding area and with outposts that can see out over the wastes themselves, Mountain Vigil is the early warning system that at times warns or protects much of the rest of Drakenvelt when danger looms. The Hulse family, long time lords of Mountain Vigil, employ renowned armorsmiths, some of them reputedly Dwarven or Dwarven-trained.

The river flowing from Mountain Vigil leads to the Wastefed Lake, home to three complicatedly interconnected lordships utterly dependant on the lake and Mountain Vigil for support. On the north shore is Tarrow’s Down, known for a flourishing chalk mine and its ageless feud with neighboring Lakedeep along the eastern shore of the lake. Lakedeep is a known destination for treasure-hunters looking to explore ruins near or even beneath the Wastefed waters. At the southwest tip of the lake is the tiny community of Zielona, site of an ancient, decaying fortress that serves as a retreat and stronghold for the citizens of both Lakedeep and Tarrow’s Down, sometimes even the more vulnerable of Mountain Vigil, in times of hardship sufficient to break down the barriers created by the perpetual petty feuding of the other lake communities.

Estermont

Occupying the southern portion of Warwick’s west coast and extending far eastward spanning the entire north-to-south breadth of the duchy, Estermont is the largest of the baronies and home to the ducal seat and capitol. It contains Warwick’s two largest cities, as well as some of its most lucrative geographical features, and is where the bulk of all wealth for the duchy resides. Estermont is ruled by Baron Logan Craigavon, who along with the Duke resides in the city of Newcastle.

Port Blackwater

Practically a nation unto itself, the dangerous streets of Blackwater are known across the world. A cutthroat port city, divided harshly into semi-autonomous districts, Blackwater is home to every manner of misdeed and dark enterprise, a seat of power so profound that not even repeated Endrani occupation ever managed to approach bringing it to heel. The port itself is ruled by the powerful and formidable Harbormaster, whose influence is total over the vital commerce which supplies Warwick with its only true window to the world beyond. Guarding the bay are smaller settlements, grown up around lighthouses and watchtowers that flank the port entry, where an intrepid citizen might attempt to subvert the authority of the harbormaster by dealing with ships before they enter the port, but woe betide any person caught in the attempt, and the Harbormaster’s men are everywhere.

The lowest classes of Blackwater settle into one of a few slums. Mostly these are beyond the city proper, in the undesirable land to the south of the great River Vandalus whose mouth cuts the city in two, but nestled along the banks of the river lies the most urban and notorious of those slums, the Rookery of Kings. Every vicious rumor attributed to life in Blackwater is magnified within the Rookery by at least a factor of ten, and the place is so ill-regarded and hideously dangerous to enter that the Blackwater Watch itself doesn’t even try, leaving the bitter slum to the keeping of its hordes of gangsters, criminals, and desperately impoverished citizens. None tread lightly within the Rookery, a place where death comes swiftly to the unwary and the principled.

The lower classes and laborers of Blackwater tend to settle into loosely defined districts that relate either to common national origin, or groupings of related trades. The next step up the social ladder are the middle classes, merchants and those plying the more well-regarded trades, some of whom live in the market districts with their shops but others aspiring to the less fearsome neighborhoods that are almost entirely residential in the hilly area north of the river.

One hill, however, stands inviolate by the flotsam of the less than spectacularly wealthy. Most of the affluent of Blackwater cluster together in their proud manses and luxurious homes, walled into elite neighborhoods that could almost be transplanted any other wealthy city of the modern world. These neighborhoods rank their level of importance strictly along material lines, with the most wealthy being closest to the almost palatial keep of the Lord of Blackwater himself, Lord Rupert Locke, crowning the Lord’s Hill with his expansive estate.

The climate of Blackwater is one of perpetual vigilance and often fear, cutthroat competition invading every facet of life from bringing food to the table to running any matter of business or entertainment. Anything can be had for a price, and there is almost certainly someone willing to take the knees out of another for the custom. Even the temples lining the boulevards in the more prosperous parts of the city are subject to brutal competitiveness and ideological conflicts with one another. Politicking and struggle are innate to Blackwater, and the strongest prosper upon the bent backs of the weak and unsuccessful.

Newcastle

Deep in the heart of Estermont sits the capitol of Warwick, Newcastle. Though the city was flourishing as well as it could prior to Alban acquisition in 2007, that event brought about a population surge that nearly trebled the size of Newcastle in a few short years. The core of the city is ancient and oft-rebuilt, a fortress once no larger than Mourning around which the city has bloomed. Strong walls and proud edifices have withstood generation upon generation of hardship and turmoil, as Newcastle is a prime target in any conflict. Taking out Newcastle and the military organization it represents essentially cripples the entirety of central Warwick, a fact that no army passing in either direction has seen fit to overlook.

Surrounding the core are newer neighborhoods, entire suburbs built quickly with varying degrees of care from fresh young stone temples to ramshackle shanty towns at the furthest outskirts. Three nearby villages were completely absorbed in the explosive expansion, and the end result is a rambling and complex city that is a perpetual study of contrasts.

As the home of Duke Sebastion (Jinx) Lledrithcath, Newcastle is the administrative center for the duchy. The regional Commander of the Watch, Knight Commander Sherman Halford, operates out of Newcastle. His Majesty’s Fourth Army under Major General Sir Roderick Stanbridge is based out of Newcastle, as are the Royal Couriers, and almost all of the guilds and organizations of Warwick have a base of operations there.

As a city that bustles with commerce and business, bristles with military and paramilitary personnel and their dependents, and sits under the watchful eye of an able administrator, Newcastle is without question the single safest place to be in the entirety of Warwick on a day to day basis, but even so it is far from inviolate. With such rampant expansion, the bulk of the population is essentially indefensible in the event of a large-scale attack. Crime, corruption, and hardship are marbled through Newcastle’s streets as thoroughly as any city, and there is a perpetual low level of stress created by tension between long time residents and the flood of Alban newcomers.

A noteworthy feature of Newcastle is the long-standing tradition of wholesale apprenticeship of freed slaves by a particular brotherhood of skilled craftsmen. This group of artisans, regarded as marvelously philanthropic by their adherents and cunningly predatory by their detractors, take on far more than the usual number of apprentices, often without initial fee, and train them in vital skills and trades. It is also said they often house and feed entire families, but the arrangement is clearly beneficial to these businesses despite the apparent largesse, and the practice has a decided impact on the local economy.

Mourning

The fortress town of Mourning is the guardian of Estermont’s northern border, nestled up against the mountains and functions as gatekeeper against the threats of the Wastes. Those threats are numerous and battle is a way of life in Mourning. Well guarded mines supply the ore to support a flourishing trade in weapons and armor, and the people of are hardy and proud folk, though seldom long of tooth. Mourning is the largest of all settlements along Warwick’s entire northern border, and while almost always under threat and often under attack, its people take a distinct satisfaction in the rigors of their existence and a fierce self-sufficiency. Long riders from Mourning patrol out across the border, and the Watch has a substantial post there as well.

The administration of Mourning is almost military in every respect, it’s lord being a hard man who runs the whole of the town very much like the fortress itself. When in true danger, much of the town is simply abandoned as the population flees into the close confines behind the curtain wall for protection, along with many from the surrounding area. This happens just often enough that the construction of homes and business that do not fit within those walls could be considered willfully temporary, structures meant to last only a few years before they will inevitably have to be sacrificed.

Every year, Mourning holds some of the most dramatic and feverish midwinter festivals known. Even in the heat of terrible conflict, nothing can stand in the way of fulfilling momentous Yule traditions for the town of Mourning. Every eave is decked with evergreen swags, candles in every window, bonfires in the night, and traditional plays and fetes for weeks leading up to Midwinter, whereupon the town is transformed into a solemn and somber, deeply mystical observance of remembrance for the past and hope for the coming year. As with so many other aspects of life in Mourning, even celebration is conducted with almost military precision.

Other Communities

East of Mourning, nestled against another of the ubiquitous mountain ranges that form the Northern border, lies Weatherly; a well-fortified village centered around a flourishing tin mine. Weatherly is home to an interesting curiosity, a sort of martial academy utilized by militias and guardsmen from throughout Estermont. The Weatherly School is known for hard taskmasters from a variety of cultural backgrounds who provide peerless training for the small unit strategies needed for any militiaman or guard to serve against the dangers of Warwick. The population of the school serves to protect Weatherly from some of the ravages of living so near the Wastes, but training is often live-fire and the casualty rate among students can become unsettling during particularly bad seasons. Those who graduate are well regarded, battle tested, and sought after for the quality of their education.

East and south of Weatherly, but still within flight distance of Mourning, the village of Stoke lies in the rugged foothills of northern Estermont which make an ideal home for their herds of sheep, goats, and rangy cattle. Stoke produces fine wool, both rough and in finished goods, but is forced by its location to support a population as much warrior as herdsman, to keep their livelihoods safe. In times of danger they will drive herds into box canyons and retreat into underground catacombs or cave systems, some parts of ancient ruins on which parts of the village were built. The town is, unfortunately, burned to the ground by raiders as often as once a decade, but in spite of this is rebuilt in precisely the same spot each time.

Along the Vandalus east of Newcastle lies the true breadbasket of Warwick. Hugging the river and the road to Brunswick, a series of agricultural towns are strung like glittering beads along the outlandishly, almost unnaturally, fertile soils. The fabulous wealth of foodstuffs makes for flourishing communities, well guarded by His Majesty’s Army and by their own stolid citizenry. Brighton and Hovis are among the largest of these towns. Brighton, nearer to Newcastle, is a surprisingly compact arrangement for an agricultural community, with an almost regimental approach to the safety of its lands and fields. Several days east up the road, Hovis, by contrast, is a vast and disorderly sprawl creeping up valleys in every direction and relying more on magical interventions to keep its people safe. It is widely known that the Lord of Hovis is a powerful mage in his own right, and rumors of his prowess and vindictive creativity run rampant enough to offer some degree of protection all on their own. All of these communities are subject to the usual hardships of an agrarian township, but with the added Warwick Flavor of constant vigilance and strange, erratic hazards and hardships that might swoop down upon them at any time. No matter how well protected and prosperous a region may be, farming in Warwick is never for the faint of heart.

South of Newcastle in the swamplands well east of Blackwater, large settlements are few and far between. The land is inhospitable and subject to both natural and unnatural changes of landscape, often very sudden. But there are rewards to living in the swamp, as evidenced by the continuing existence of Direwolf Glade. Perched near the divergence of the Vandalus at the Keening Morass, Direwolf Glade is a reclusive community of hardy folk who brave the hideous dangers of the swamps and even the morass itself for the rich and often beautiful clay to be found in the area. Fine pottery and ceramics are made by the ton by this queer lot, and exported to obtain any necessities the swamp itself does not provide. The folk of Direwolf Glade often picks up the entire settlement, kiln stones and all, and move between a handful of locations along the lesser Vandalus (the entire reach sharing the name of the lordship), to accommodate the changing waterways and seasonal hazards of their land. It is widely speculated that the lord of Direwolf Glade is half-direwolf himself, and can run with the packs of vicious predators as though one of their own to ward off unwary travelers. The town is also said to keep wolves, dire or otherwise, as watchdogs, and to feed their pets any brigands or bandits who try to take refuge in the vastness of the Morass.

The drier forests nearer to Blackwater are perhaps less teeming with natural hazards, but are as a consequence rich with outlaws, smugglers, and dangers of the semi-civilized variety. One haven against this kind of rough living is the small town of Hillsbend, a close-knit and relatively peaceful place with the unique specialty of producing very good paper, which is in profound demand in Blackwater. The town enjoys its peaceful existence thanks almost entirely to the Hillsbend Grove nearby, an honest-to-goodness grove of very serious Druids who do not take kindly to those who interfere in the forest territories they claim as their own.

Daneholt

Beyond Estermont lies the second largest barony of Daneholt, ruled by Baron Eadraed Hawkes, the former Lord of Bitterfield elevated to the baronial seat in 2011. Spanning from the mysterious chasm of Dane’s End at the extreme north, all the way to the dismal scrubland and desert of the southern border with Doomstadt, Daneholt is a geographically diverse region supporting an equally diverse population and features some of the most unusual geographical landmarks in Warwick. Its northern flank is less well protected by mountains than either of the western baronies, and little of the southern reaches of the barony or habitable even by the stalwart standards of Warwick, but central Daneholt remains not only livable, but a sought after destination.

Brunswick

The largest settlement in Daneholt, and indeed eastern Warwick entirely, is the modest city of Brunswick on the vast artesian lake that is Ullswater. With the finest, cleanest water in Warwick readily at their disposal, Brunswick is a city that boasts a reduced influence from the tainted malaise so prevalent through all of Warwick’s landscapes. The high moor country around the lakes is rich with life of even the modest and ordinary sort. Unfortunately, the prime real estate upon which it resides makes Brunswick a hotbed of contention that has forced it to build into a fiercely guarded stronghold.

Though far from the massive size of Newcastle, Brunswick is nevertheless a city true. It is considered by many to be the beating cultural heart of Warwick, far inland from the stain of Blackwater commerce and protected to some degree from the influence of the Wastes. With its innate “cleanliness,” Brunswick is an attractive spot for many faiths, and there is an abundance of temples, even monasteries and large enclaves, representing a plethora of denominations and sects. It is also an appealing location for magical study and research, libraries of information, and a location that is attractive to families and craftspeople. When in particularly dire danger from Wastes creatures pressing south, it is not unheard of for vast portions of the Brunswick population to pile onto barges and float out to the center of the lake, anchoring to permanent moorings on the rocks there, to wait out whatever difficulty may arise as a floating city. That security measure helps lend additional comfort to Brunswick’s citizens.

In generations past, Brunswick was a prized colony for the Endrani, both for its attractive location and as the perfect nearly-civilized location to have a large scale slave market for those being culled from the Wastes. The culture of slavery that is in no small part responsible for the city’s prosperity and cultured demeanor has left its indelible stamp on the construction of much of the city, from the way the streets are built and homes themselves, to great market plazas clearly meant for other-than-beast trade. Some of these are now converted to theaters, public squares, or are being built upon, but the evidence remains.

The most significant dangers to Brunswick are posed by large-scale invasion from the north, something that happens with unpredictable frequency. Though well defended, the city has been breached more than once in its history, and the scars of those invasions are slow to heal.

Bitterfield

South of Brunswick, at the very border of Doomstadt along the southerly trade road out of Newcastle lies the town of Bitterfield. A fortress town, Bitterfield has been taken and retaken so many times in its tempestuous history that the entire place has a sort of beaten, broken down appearance. This is not enhanced by severity of the landscape, and its residents are notoriously, almost proudly cynical.

Through the rigors of conquest and endless rounds of smuggling and slave trade, both illicit capture of slaves and their illicit escapes, Bitterfield is riddled with secret passages, hidey-holes, hidden tunnels, and concealed ways too numerous to count. Though this property is far from secret, the passages are so numerous, so frequently altered or added to, and often in poor repair that they remain effectively lost to obscurity and are no doubt used for such purposes to this day.

Every corner of the battered fortification has its ghosts and ghost stories. Slaves walled in to a hidden room and never retrieved, bandits lured into a passage that had been brutally trapped, and countless other tales of misery, woe, and restless dead linger in popular culture and give the town an additional aura of eeriness and foreboding.

Other Communities

In the northwest corner of Estermont near the waters of the Vandalus lies the enormous Orc stronghold of Bad Rock. Once the bane of every living thing within three days brisk march, the Bad Rock Orcs were famously won as allies to Imagicka by Sir Hestor Craigavon, grandfather to the present-day baron of Estermont. Though still ferociously independent and far from friendly, Bad Rock focuses its offensive capabilities north of the border, and is a staunch defender of that border much to the relief of the rest of Daneholt. Bad Rock has even begun over the last generation to dabble in conventional commerce, finding a market for their durable hide armor, as well as the furs, hides, and relics from warped waste creatures they hunt. Most significant, however, is their trade in knives. No matter the material of their construction, be it steel, iron, copper, obsidian, even unique hardwoods… Bad Rock orcs make incomparably fine knives. They know it, however, and charge accordingly.

Far to the east of Bad Rock, within a two day hike of Dane’s End, is the queer community of Swierszczow. The citizens of this small town have long considered themselves “guardians of the gap,” but kept a wary and superstitious distance from it, perpetuating the myths and legends of the place. Over the last three decades, however, Swierszczow has become something of an attraction to a variety of people including alchemical researchers, mages and their students, even bizarre cults, treasure hunters, and history buffs. There exists an uneasy relationship between the long-time residents and those, for better or worse, intent on studying the nearby depths and their curious emanations, with a great deal of infighting and accusations of curses and meddling flying about. Coupled with the innate danger of living in the extreme north of Daneholt, Swierszczow is not a friendly or inviting place to live. The best that can be said for its defenses is that having an excess of alchemists in any community is bound to come in handy eventually.

Even closer to Dane’s End and all of its mysteries lies the ruin of Moorhadath. Though it is under exploration from time to time, it is widely thought to be cursed, haunted, unsafe and/or a completely awful place. Occasionally speculated to be the remains of some civilization overrun by the mage-lords of legend, those who dare to investigate it more than once will swear it has been rearranged or altered each visit. Many vanish there, or return from expeditions altered in some deep way from which they never seem to recover. The ruin is essentially untraceable, no good evidence for its original inhabitants yet found, but periodically there are treasures and curiosities unearthed there that keep the adventurous coming from time to time, in spite of the risks.

On the southern shores of Ullswater is a tiny “resort” village, Solace Springs. A sheltered community built around a natural hot spring, it was formerly a favorite retreat for matrons resigned to the bitter north. Renamed within the last twenty years, it now it supports a strong presence of healers using the soothing waters for long-term care, and otherwise supports itself by subsistence and a modest trade in the mineral waters of the springs. Solace Springs is utterly dependant on Brunswick for defense, and while the residents aim to be peaceful they have more than once been driven onto the lake or entirely eradicated by hazard or brigand attack. The community is dutifully retaken and reestablished, as the healing properties of the waters are undeniable.

Downstream from most of the larger lakes of central Daneholt are a number of small barbarian communities dependant on the clear waters pouring down from the moor country for their survival. One such is Lachendershlund, near the confluence with the Vandalus. The name, meaning “laughing maw,” is drawn from a large eddy around a sizable crag mid-stream which creates a dangerous and eerie hazard in the waterway resembling nothing so much as a great mouth, ready to consume any that approach. Lachendershlund is typical of the river towns in that it is populated by hardy, rugged folk that fish the river and hunt its banks paying little heed to anything else. These river folk have a much stronger cultural resemblance to one another than other populations in Warwick, very much true to their own tribes and unwelcoming to outsiders, but willing, grudgingly, to interact in a limited fashion for trade.

In the south, exactly two days by wagon north and west along the road from Bitterfield, lies Blight Station. A resupply post and stopover point for those traversing the arid grasslands, Blight Station is built around a small oasis of barely potable water, surrounded by the warped and twisted remains of a long-dead copse of scraggly trees. Despite the inhospitable surroundings, the tenacity of the people of Warwick reared its head and a small town arose at this common stopping point for wayfarers. The water of the spring feeds feeble gardens. The plains, though poor fare for herd beasts and hopeless for farming on any scale, do furnish small game. And most attractive about the spot; a never-ending supply of poisonous snakes offers a uniquely effective deterrent to roving bands of anything, perhaps explaining the appeal. Blight Station is an excellent example of how life in Warwick will spring up and flourish in any place it can get a toehold, sheltered by even the merest ghost of security.

Freeholt

Anchoring the east and most gods-forsaken back end of Warwick is the small barony of Freeholt, ruled by Baron Anthony Talbot. Hopelessly remote, literally trapped between a rock and a hard place, Freeholt is a brutally remote place to live, convenient to nothing. Its greatest asset is liberty, for in the far reaches of noplace anyone wants to be, freedom to live as you see fit is available in spades. The most sparsely populated of all the baronies, Freeholt is an undesirable scrap of half-tamed back-country that nevertheless is of crucial strategic value to Warwick.

Newhaven

For a slave on the run from Doomstadt up the road through Signal Hill, Newhaven is the first place one can really stop and take a breath, dare to feel comfortable, or even think of calling it home. There are small hamlets along the road, but the walls of Newhaven are a mark of passage. In Newhaven’s past, it was a rallying point for slaving expeditions into the wastes, the most northern point where a Doomstadter could put her feet up and relax before venturing into the wilds. Thus littered with the scattered remains of slave pens and other unpleasantness, Newhaven has thrown off that heritage and stolidly maintains that sense of security, the welcoming sense that once a slave has come that far, they’ve made it. From Newhaven the road turns southwest into the rest of Warwick, but from that point forward a freed slave can feel free. Though not sizable by the standard of the other baronies, Newhaven is the second largest town in Freeholt. It is well defended and fortified, and provides some sanctuary to those few hardy souls in the minute villages scattered nearby that would choose to take shelter there against invasion or harm.

Newhaven is a poor community, without strong economic footing and with a chief export of labor. Its inhabitants are relatively generous with what little they have, when it strikes them to be, but it is not a truly prosperous place. A lack of money or luxury goods does not imply a lack of vigilance, however, and no matter how simple a weapon may be in the hands of a Newhaven militiaman, he will know how to use it with deadly efficiency and all the skill hunger, fear, and pride can provide. No one will fight harder for his home than a Newhavener, because few fought so hard to have a place to call their own.

Signal Hill

In the never ending bloody chess game that has been the history of Warwick, Signal Hill has always been a crucial piece. Its watchtowers provide a rapid alert system for whatever occupying force of the day happens to possess it, and it is presently a well-garrisoned rallying point for troops being funneled into the extreme east of Doomstadt. Having seen not only the never-ending ebb and flow of war and conquest, much like Bitterfield, but also a substantial amount of external conflict and hardship, Signal Hill is a thoroughly battered stronghold. Though kept in repair, it lacks the architectural complexities, nooks, and crannies of Bitterfield.

Signal Hill, thanks to its position so close to the Dragonspine, sees a great deal more exotic foreigners than perhaps any place in Warwick besides Blackwater. Commerce is maintained with the dwarves, and even Shalkarans are not entirely uncommon there, along with some truly odd travelers coming out of the mountains.

Other Communities

Most of the villages and hamlets of Freeholt are insignificantly small, and no matter how well they are defended they tend to vanish entirely at intervals, new communities springing up in other places or the same ones. Everything vile or dangerous that can stampede out of the Wastes will do so, and Freeholt does its best to fend them off.

In the central reaches of Freeholt, Sorrofeld is one of a few hardy burgs struggling with the challenges of agriculture. Without the benefit of abundant water or rich soils, every acre is hard-won. Each field must be walled in with stone to protect it, and the farmers typically sow as many as five different sorts of grain into the same fields, in the hope that at least one will flourish and not fall victim to disease or wither before harvest. And those who live in Sorrofeld are as tenacious as their environment dictates.

East of Newhaven near the edge of the blasted desert scablands that mark the northeast corner of Freeholt is the relatively new-formed town of Fool’s Errand. As more and more become interested in venturing into the Wastes by way of the wide-open gap in the mountains that is Freeholt’s northern border, a group of such explorers began building up a sort of permanent base camp that bloomed into a proper community, of sorts, that attracts more of the same. A secure place for such adventurers to retreat to, and a good branching out point, Fool’s Errand is thick with guides and trackers of every description, anything a wise explorer might require, and quite a bit more that appeals to the sort who won’t likely return. One thing keeping this motley community safe is the enormous skill and knowledge of its inhabitants who have struck bargains and made peace with numerous indigenous peoples due north in exchange for if not protection than at least excluding the small town from their raids. Though not infallible, this limited protection keeps Fool’s Errand secure from, at least, the most highly organized units amongst the usual suspects.

At the extreme east end, right in the foothills of the Dragonspine, is the trading post The End. While it has a name in Dwarvish that is more flattering, the human population of the area has fairly prosaic attitude about it, calling it in one language or another the Arse End of Nowhere or simply The End. The post is built almost entirely underground, a necessity with all the foul things prowling the surface of the mountains this far north, and the entrances open out into the southern tip of the great deathly scablands, theoretically another protective measure. It is in this location that most trade with Dwarven merchants takes place, and being completely removed from any semblance of civilization there is little to amuse the senses or spend money on. It is often attacked from above OR below, and only the commerce with the stellar Dwarven craftsmen gives cause to keep the place manned at all. A person with the right motivation can become very wealthy very quickly in The End, if shrewd enough a negotiator and smart about what is needed out in the rest of the surface world, but few can bear the harshness of the environment or the constant paranoia and threat for long, so a fortune had best be made quickly.

Social structure

The society of Warwick is widely varied and lacks a single rigid hierarchy. At the top of pecking order are the Alban nobility, or the retained and elevated nobility in place, who rule over their own lands. Each is fairly autonomous, however, and the distance separating a lord from his people varies enormously from one region to the next.

Some places have retained Endrani Expats as lords and ladies, and in those locations the separation tends to be a vast gulf. Other places have people hardly more important than a city councilperson functioning in a lordly capacity. Most lie somewhere in between.

Another consideration in Warwick social structure is the sheer number of independent cultures and peoples scattered throughout. In an isolated culture, even one installed in a larger community, the highest authority belongs to the tribal or sectarian leadership, possibly religious figures, and the authority of the technical noble is only an inconvenience and not a real distinction. This likewise applies to the tribes of goblinoids, barbarians, and other wildlander cultures that are scattered throughout the unincorporated spaces of Warwick. While technically within the borders of Alba, they do not recognize its authority at all and have only their small internal structure.

And yet another divergent path to importance and influence lies in the internal hierarchies of organized crime, which again march to their own drum and recognize only their own authority. This is as true for roving bands of outlaws as it is for the powerful criminal enterprises lurking in the underbellies of all Warwick’s major population centers, and the authority of these figures extends far beyond other criminals to include all of those weaker than themselves who yield to their protection or cannot escape its shadow.

Clerics of varying religions hold varying amounts of status according to their own following and location, but do not hold a prominent place in any sizable Warwick culture.

In general, the importance accorded to a person varies along lines loosely drawn by long-standing Imagickan standards. Simple laborers are of the least status, along with the mentally challenged or deranged. Barely above the drone-class come farmers, no matter how much more challenging it is to farm in Warwick than elsewhere, and just above them in general perception comes the skilled laborers who do more specialized tasks. Above that level importance diverges into different branches, with places for true craftsmen, entertainers, clerics, warriors, mages, really good mages, and so on – but the importance of an individual varies along these well-worn paths and is essentially similar to Alba in that way, with one important caveat.

Freed slaves tend rate themselves differently than the usual Alban citizen. The simplest way to express the way importance is measured among the freed is to say that whoever traversed the hottest fire, the harshest climb, the greatest hardship on the road to freedom will be treated with the most respect, with no importance whatsoever attached to skill, profession, age, or even necessarily wisdom. Tenacity is the trait of choice against which status is measured.

Culture and Customs

Being an ethnically diverse territory, Warwick does not have much in the way of its own distinct culture. All who choose to live in Warwick must be hardy, usually determined, often enterprising. People in Warwick tend to be tough, uncompromising, and slow to trust. They are frequently very independent in nature, and most deeply despise the practice of slavery. The average Warwick citizen will swiftly associate lesser impediments to freedom and evidence of authority with memories of slavery or thoughts of being constrained.

The more recent transplants to Warwick, product of the great population surge since 2007, tend to be the adventurous, hardy, or desperate of Alba eager for the reward of space, privacy, freedom, or wealth and willing to sacrifice no small part of their personal security to get it. While they lack the deep-seated mistrust of outside authority figures that the long-term residents almost treasure, these immigrants from Alba can usually sympathize enough with the ideas of the natives to methodically insinuate themselves into the land.

Prejudices can run deep through the wildly varied populations. Some loathe all goblinoids with a passion after having suffered years of attacks by them in some form or another. Others are sympathetic to the goblinoids and want to improve relations with them. Many despise Endrani, others do not care. Most distrust Dragoons and outright hate Dhampari, but then so does just about everyone in all the lands of former Imagicka. Human remains the normative ideal, but Sidhe Taelgranis and Gaelbraugh or not ill received, and Palateth enjoy slightly less prejudice against them in general throughout Warwick.